The internet is a minefield of bad Gordon Ramsay Pasta and Rice Recipes. They tell you to rinse your pasta, to dump cream into your risotto, to serve a watery sauce next to a pile of naked spaghetti. It’s culinary malpractice. For years, I followed that advice and was left with clumpy, bland pasta and risotto that had the texture of school glue. I got tired of the failure.

The secret to restaurant-quality pasta and risotto isn’t a magical ingredient; it’s a philosophy. It’s a set of non-negotiable techniques that Gordon Ramsay himself follows religiously. It’s about respecting the “liquid gold” of pasta water, mastering the art of “al dente,” and understanding the transformative power of finishing your pasta in the sauce. This is the blueprint. Once you learn this method, you can execute any of his iconic dishes with confidence and precision.

The Method: Why The Authentic Gordon Ramsay Pasta and Rice Recipes Work

These dishes seem simple, but their perfection lies in executing a few key principles flawlessly. These techniques are designed to maximize flavor and, most importantly, create the perfect texture—that creamy, glossy sauce that clings to every strand of pasta, or the flowing, unctuous river of a perfect risotto.

1. “Liquid Gold”: The Starchy Water

This is Ramsay’s number one rule. After you boil your pasta, the water left behind is cloudy, salty, and full of starch. He calls it “liquid gold” for a reason. This isn’t dirty water to be thrown away; it’s a critical ingredient in your sauce. When you add a ladle of this starchy water to your pan of sauce, the starch acts as an emulsifier and a thickener. It helps the fats (like olive oil or butter) and the water-based components of your sauce bind together into a single, cohesive, creamy entity that coats the pasta beautifully. Throwing this water down the drain is like throwing away the key to the entire dish.

2. The Art of “Al Dente”

“Al dente” translates to “to the tooth.” It does not mean crunchy or raw. It means the pasta is cooked through but still has a firm bite in the very center. This is not just a textural preference; it’s a structural necessity for the next step. You must pull the pasta from the boiling water about a minute or two before it’s perfectly cooked, because it is going to finish cooking in the sauce. If you cook your pasta all the way through in the water, it will be overcooked and mushy by the time you serve it.

3. Finishing in the Sauce

This is the technique that separates amateurs from chefs. Never serve sauce on top of pasta. The two must become one. The process is a beautiful, frantic dance: the al dente pasta is pulled from its boiling water and transferred directly into the pan with the waiting sauce. Add a ladle of that “liquid gold” pasta water and toss, stir, and shake the pan vigorously over the heat. In these final 60-90 seconds, three things happen: the pasta finishes cooking to perfection, it absorbs the flavor of the sauce, and the starchy water emulsifies everything into a glossy, restaurant-quality coating. This is the soul of authentic Gordon Ramsay Pasta and Rice Recipes.

4. The Risotto Stir

For risotto, the principle is similar but the execution is different. The creaminess of a true risotto does not come from cream; it comes from starch. You must use a high-starch rice like Arborio or Carnaroli. The method is patient: you add warm broth one ladle at a time, and you stir. The constant, gentle stirring agitates the rice grains, encouraging them to release their natural starches, which in turn thickens the cooking liquid into a creamy, velvety sauce. It’s a labor of love that cannot be rushed.

Mistake Watchouts: I Failed So You Don’t Have To

My kitchen has been a graveyard for pasta and rice dishes. I’ve made soupy sauces and gluey risottos. Learn from my experience.

- Mistake #1: Drowning the Pasta. I used to think more water was better. I’d use a giant stockpot for two servings of spaghetti. The result? The starch from the pasta was so diluted that my “liquid gold” was just cloudy, salty water with no thickening power. The Fix: Use less water than you think you need. For a standard pack of pasta, 4-6 quarts is plenty. You want the water to be noticeably starchy when the pasta is done.

- Mistake #2: Rinsing the Cooked Pasta. A cardinal sin. I did this for years because I thought it stopped the pasta from sticking. All I was doing was rinsing away every molecule of the surface starch that is essential for helping the sauce cling. It’s like washing the glue off an envelope before you try to seal it. The Fix: Never rinse your pasta. Ever. Transfer it directly from the pot to the sauce. The starch is your friend.

- Mistake #3: The “Dump and Pray” Risotto. I was impatient. I would toast the rice, dump in all the broth at once, cover it, and pray. I was left with a gummy, porridge-like mess. The rice on the bottom was mush, and the top was undercooked. The Fix: There are no shortcuts. Add warm broth one ladle at a time. Only add the next ladle after the previous one has been fully absorbed. And stir gently but constantly. This is the only way to achieve the correct texture for Gordon Ramsay Pasta and Rice Recipes.

The Essential Pasta & Rice Recipes to Master

Once you internalize the core philosophy, you can apply it to Ramsay’s most iconic dishes. These are the recipes that form the backbone of his mastery in this category.

- The Perfect Risotto: The ultimate test of the slow-stir method. It teaches patience and the art of building creaminess from starch, finishing with a final mantecatura of parmesan and butter off the heat.

- Classic Spaghetti Carbonara: A pure application of the emulsification technique. There is no cream. The sauce is created from egg yolks, pecorino cheese, and hot, starchy pasta water.

- Spicy Sausage Tagliatelle: This dish is a masterclass in finishing the pasta in the sauce, allowing the wide noodles to absorb all the rich, savory flavor.

- Quick Garlic & Chili Linguine: A simple, elegant dish that lives or dies by the quality of your “liquid gold” to create a glossy, perfectly emulsified sauce from little more than oil, garlic, and water.

Plating and Execution

Ramsay serves with clean, confident, and simple presentation.

- For Pasta: Use a pair of tongs and a large ladle. Grab a portion of pasta with the tongs, place the tips of the tongs in the bowl of the ladle, and twist, creating a neat, tight nest. Gently slide this nest into the center of a warm pasta bowl.

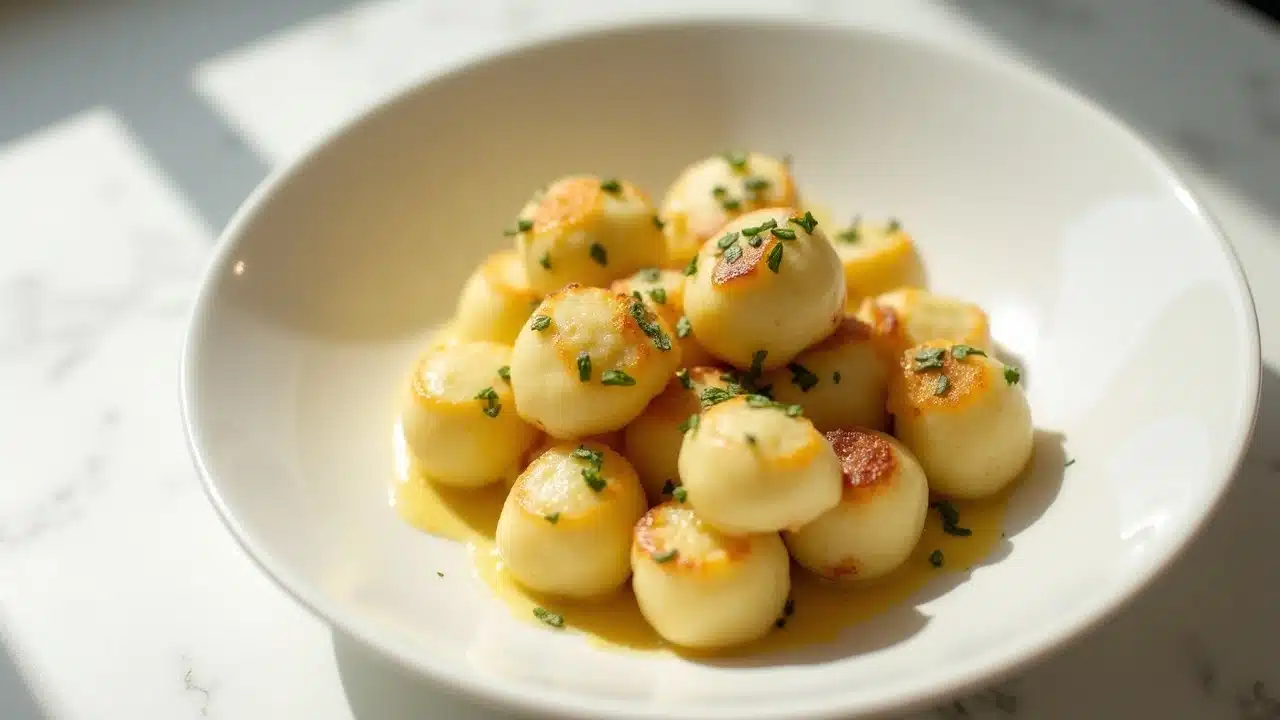

- For Risotto: The risotto should be “all’onda,” meaning “on the wave.” It should flow. Spoon a generous amount into the center of a warm plate. Give the bottom of the plate one sharp tap on the counter. The risotto should spread out in a perfect, even circle. It should not be a stiff, static mound.

- Garnish with Purpose: Finish with a drizzle of high-quality extra virgin olive oil, a grating of fresh Parmesan or Pecorino cheese (never the pre-grated dust from a can), and finely chopped fresh parsley or torn basil leaves.

Recipe FAQs

What’s the difference between fresh and dry pasta?

Dry pasta is typically made from just semolina flour and water. It has a firm texture and holds up well to heavy, robust sauces. This is your go-to for most Gordon Ramsay Pasta and Rice Recipes. Fresh pasta is made with eggs and flour, is much more delicate, and cooks in a fraction of the time. It’s best suited for lighter butter or cream-based sauces.

How salty should my pasta water really be?

Ramsay’s famous line is “make it as salty as the sea.” In practical terms, this means about 1 to 1.5 tablespoons of coarse sea salt for every 4-6 quarts of water. The pasta absorbs the salt as it cooks, seasoning it from the inside out. This is a critical step, as it’s your primary chance to season the pasta itself.

Can I use cream to make my risotto creamy?

You can, but Ramsay would call it a shortcut that masks true flavor. The authentic creaminess of a risotto comes from the starch released by the rice during the constant stirring process, and the mantecatura at the end—vigorously beating in cold butter and parmesan cheese off the heat to create a final, beautiful emulsion. Using cream is a cheat that results in a heavier, less nuanced dish.